Adapting to Doing Business in Latin America as a Foreigner

Latin America is an intoxicating region to live and work in as a foreigner, but getting the most out of it requires adjustment. From several years of experience, here are some pointers on how to succeed.

An enigma, on the cusp of potential, incredible biodiversity, an oasis away from western geopolitics.

Just a small, generalised selection of factors that allure foreigners to Latin America. Guides about moving there tend to lean towards practical lifestyle advice. But what about building a career?

Presented here is a collection of pointers for how to build a platform for success as a foreigner, structured around the following themes:

- Porting ideas from the west

- Family business affairs and Latam Guanxi

- Different expressions of class and culture in the workplace

- Impact of disparate education systems

- Navigating expat life

My Latin American Journey

I lived in Colombia and Mexico for several years and, career-wise, it was an enlightening period.

After studying an MBA in Spain, a chance opening resulted in a consulting contract in Bogotá, which felt like a very aligned opportunity. I had always wanted to work in a rapidly-evolving emerging market country, and Colombia ticked many boxes.

Over the period 2015-18, across Colombia and Mexico, I did the following:

- Scale-up consulting for a Colombian firm that helped SMEs formalise and expand

- A stint at a local VC firm that was fully-invested and planning next steps

- Advising and building out the financial capabilities of a Colombian logistics startup that has since seen a 20x valuation increase

- Remote and local freelancing strategy consulting

- Mentoring in local accelerators and creating educational courses

- Working on a continental-wide boutique hostel concept

Now having left for good, the time has allowed for reflection. It was by no means a perfect stint, with many ups and downs that required adaptation.

Ideas from the West

In the entrepreneurial field, I observed foreigners following two kinds of paths in Latin America:

- Taking an idea from home and applying it locally

- Following a very mission-based crusade to solving a social impact issue

Both tended to omit the crucial steps of local idea validation. The predicament also exists for local investors who live abroad and take inspiration from ideas proliferating developed world markets. Investments in clones are popular, but often get niche uptakes just from upper-class customers.

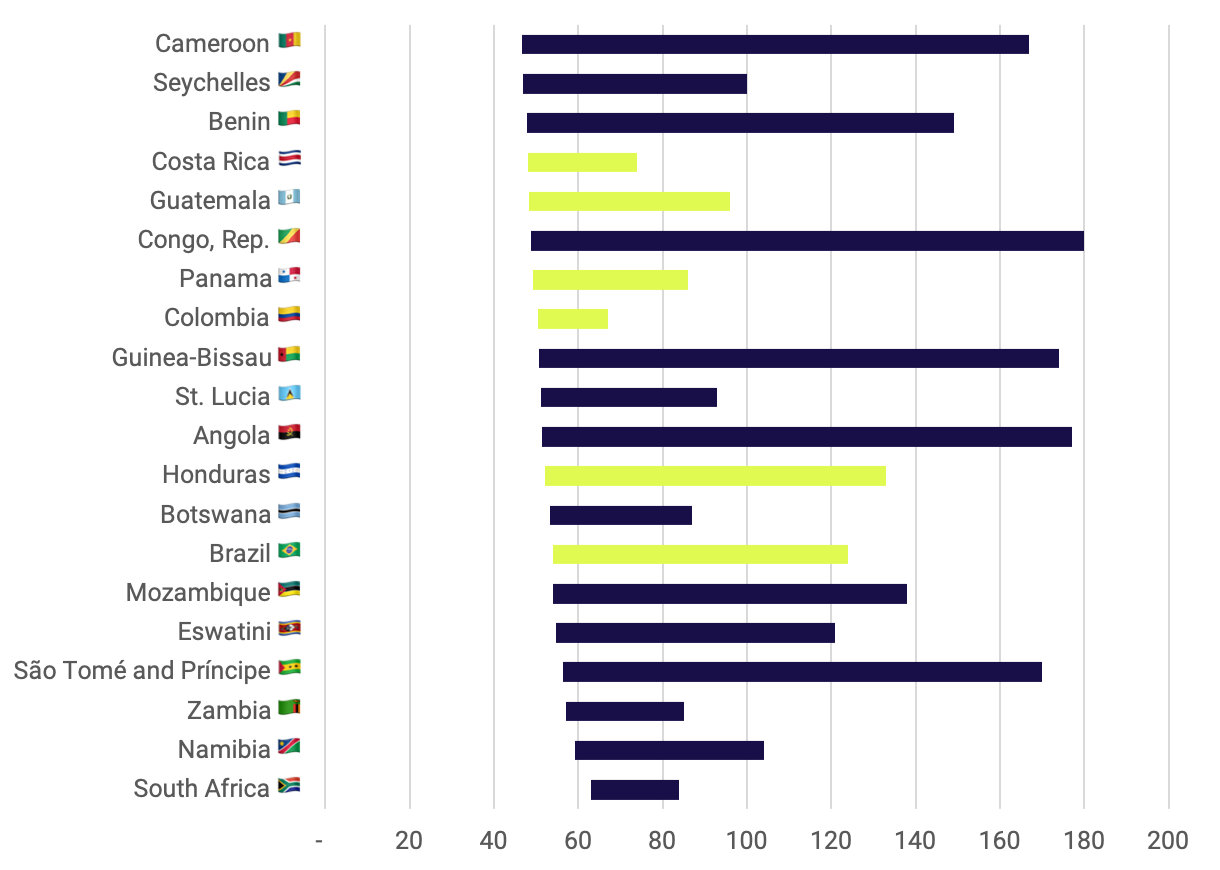

In 2018, Colombia had a Gini index of 50.4, which ranks in the top 10% of countries for income inequality (South Africa is highest at 63.0). Colombia can feel like two economies, coexisting inside the broader concept of nationhood. Yet, the disparity does not come at a compromise of entrepreneurship; compared to its Gini peers, Colombia is ranked highest (67 out of 190) for its ease of doing business. Panama and Costa Rica score strongly too:

Delta Between Highest Gini Index Countries' Scores (2010-2019) and Ease of Doing Business Rank (2019)

Finding an idea that can transcend the sub-economies and appeal to all should be a north star for anyone taking a business idea to Latin America.

Familiarise Yourself with Family Business Affairs

During an MBA course about family business, I struggled to find a large, successful example of one from the UK. After eventually settling on JCB (albeit, a great choice) it instilled uninitiated insight into the benefits of family firms.

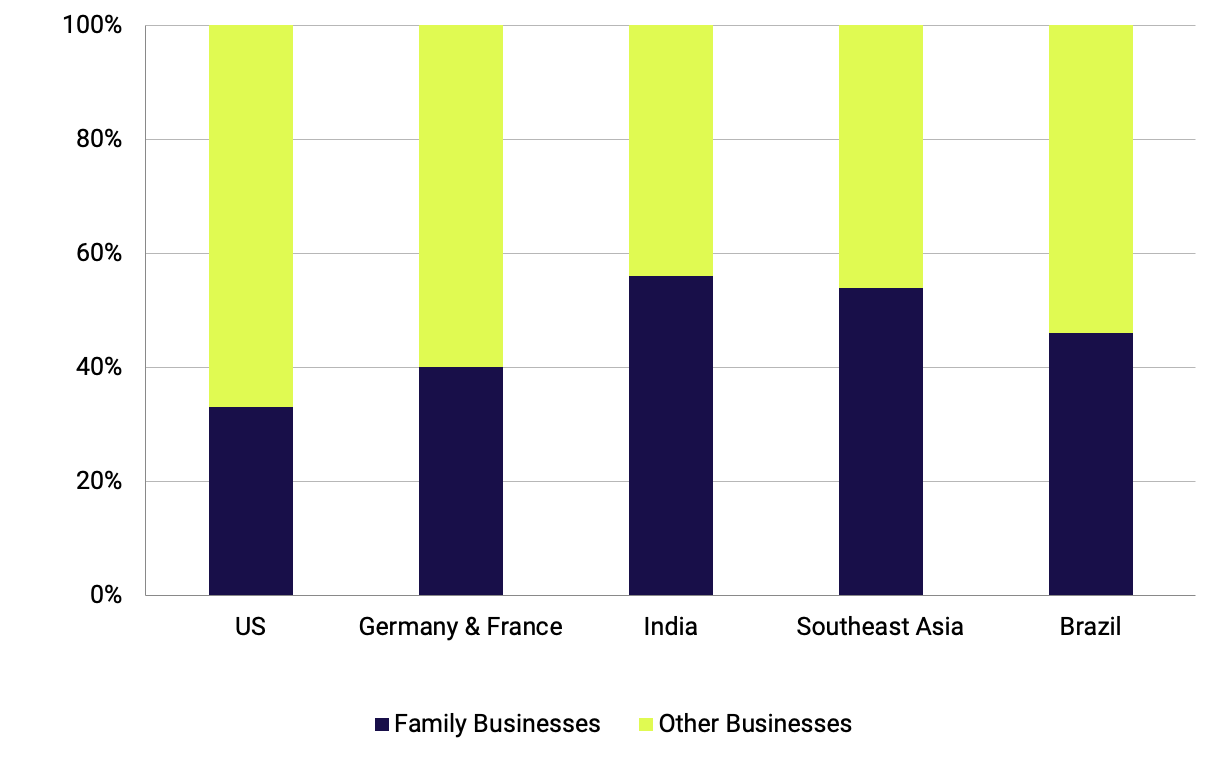

In Latin America, many successful businesses are privately-run conglomerates controlled by founding families. Indeed, this is a common trend across emerging markets.

Family Businesses are More Prevalent Among Top Companies in Emerging Markets

Throughout my time, I would encounter family businesses across a range of situations. Either as clients, co-investors in VC or socialising with friends who were part of such families.

The threads of succession and decision making across diversified operations result in family businesses being very heterogeneous entities. In Latam, where countries often switch from distinct government ideologies, a closely controlled family business with generational visions, is a more steady ship to be sailing.

A big mistake I saw with foreigners in Latin America was taking their paradigms of big western corporates and wrongly applying them to family businesses. Such as:

- Underestimation: Assuming unsophistication, either borne from unfamiliarity, or flippancy amassed from overzealous Sopranos watching.

- Upsetting the apple cart: Family groups, divided into individual fiefdoms, are complicated beasts. Picking a strategic entry point can be more fruitful than going straight to the external-facing top brass.

- Lack of big picture thinking: A western view is to present opportunities under auspices of making - or saving - money and assuming hard facts will prevail. With family businesses, place more emphasis on strategic narratives, such as tangential group benefits and intent to build lasting relationships.

For example, Liftit, a Colombian logistics startup that I advise, eschewed the traditional route of raising a concentrated seed round from traditional VCs. Instead, it fundraised from private investors, often who had family businesses that subsequently became customers and evangelists. Liftit presented not just an investment opportunity, but a relationship for supporting affiliated logistical needs.

Latam Guanxi

Oxford Languages defines the Chinese phrase Guanxi as:

The system of social networks and influential relationships which facilitate business and other dealings.

The phrase has a similar resonance in Latam culture, where building cooperation and reputation takes great importance in business.

During the MBA, while Europeans were talking about job applications and lamenting bank balances, Latin Americans were mixing business and pleasure, socialising but also making introductions and discussing opportunities.

One tactic that worked for me when building my network in Colombia and Mexico was to work off a "give first, ask later" mindset. I found that helping a new connection out with no strings built stronger foundations, which down the line, elicited unexpected reciprocity.

Foreigners in new lands tend to spray and pray when making connections, trying to get down their to-do lists. Instead, be decisive and virtuous when forming relationships: Pay it forward.

Comprehend the System of Class

In Europe, class and status prejudice abound, but the heuristic rules make for subtle weaponisation. The elite private school, Eton, taught 20 of Britain's 44 Prime Ministers and 44% of the population believe where you end up in society is based on your background.

In Latin America, class is a far more explicit badge, which requires adaptation.

Colombian utility tariffs link to a system called estratos, where charges scale-up based on the desirability of the underlying property's neighbourhood. So the rich pay more - sounds good, right? While egalitarian in design, the consequences are a culture of egregious social profiling. As soon as you know someone's address, you can pass judgement on their wealth, health and education. One client discarded CVs for such reasons.

Foreigners fit into the system and, understanding their role is a necessary step to take. In social situations, I was seemingly always asked initial questions of "where do you live?", which were vague attempts to ascertain, tenuously from my address, if I fit the profile type of a backpacker, English teacher, diplomat, etc.

At times, the status of being a strange foreigner who spoke the language elevated me above my paygrade. Other times, it was more akin to feeling like a shiny trinket, out for show, but back in the box later. If you do feel elevated, don't be arrogant or naive and read between the lines of the situation.

Workplace Dynamics

Hierarchies in local businesses tend to be flat and operate on a very transactional nature. Low-level staff who commute for hours to get to a job paying minimum wage promptly leave at 17:00. Management lament about apathy, but the transaction is two-sided: Often little in the way of vocational development is offered to staff.

We would have fortnightly meetings to discuss progress at our consulting company. Agendas would regularly digress into passionate debates with management about the direction of the company itself, which would cause friction and awkward breaks. While our goals were noble, we were taking a western norm and applying it in a different culture.

British and American employers instilled me with the mantra that blame and praise are the double-edged sword of responsibility. Yet, in Colombia, I saw a working culture of building consensus, saving face and one-way hierarchical feedback loops.

Horses for courses in terms of what works best, but not adapting your style to suit the system will result in ineffectiveness.

Getting to No

The concept of Northern European directness can go amiss in Latin America. In all situations, there is a greater need to detach from binary "yes or no" waypoints when judging progress. For six months I gullibly would assume a non-answer was just a considered purgatory, but eventually, the penny dropped.

The awkwardness of saying no, or ghosting, exists everywhere. In Latin America, it's rampant. Read the intangible signs and if they appear negative, present a face-saving "it's not you, it's me" mea culpa to at least get closure. Pay attention to:

- Ignored or delayed responses

- Apportioning delay to another factor's fault: illness, car issues, alien abduction, etc

- Running rings with bureaucratic requests

- Informal communication through channels like WhatsApp, instead of official email

Parallel Education Systems

In one consulting role, I interviewed job candidates on behalf of the client. I would sift through five-page CVs, which, while diligently made, were robotic in design (what does "56% fluency in German" mean?). Interviewees had tendencies to reel off canned answers, so at times I would ad-lib opinion-based questions like:

- Should Colombia bid for an Olympic Games?

- If you were the mayor of Bogotá, would you (finally) build a metro or construct 20 hospitals?

Some candidates would parry the questions, which after some digging, it would transpire that they were reluctant to say the apparent "wrong" answer.

Latin America has the highest skills gap in the world. Religious institutions still influence antiquated curricula and progress has been slow to move from rote learning towards critical thinking skills relevant to knowledge economies.

For that, foreigners must show empathy towards the different kind of workers encountered. Clearly defining role requirements and appraisal KPIs fosters encouragement, over more free-wheeling developed-world playbooks.

Take note of the differences between state and privately educated candidates. One time, I gave a talk to a class of 12-year-olds at a private school about the Colombian economy. The kids were confident and attentive, but with materialistic questioning that belied their ages: For example, "what's better, Visa or Mastercard?"

Expat Bubbles

Expat networks have a stereotype that magnetically draws and repels hoards of equal amounts. The appeal pulls on heartstrings of homesicknesses, to abstract colonial nostalgia of sundowners with the ambassador. On the downside, you may end up trapped in an Irish pub with a group of misfits.

After starting in the "avoid" camp, eventually, I thawed to the idea and began exploring the Bogotá scene. Meeting similar-minded people and building a solid social group enhanced my experience there. Business-wise, the connections led to many opportunities to explore.

Going overweight on expat networking does, however, require guidance to the negatives:

- Most places will almost always have an imbalance of genders. For example, if the area is hot on natural resources, teaching or banking.

- Bonds to the country often correlate positively with intellectual curiosity. Someone with a spouse or business will have more local insight than a skittish digital nomad.

- There is a survivorship bias element to expats in emerging markets. Underachieving types proliferate, who, in a Peter Pan existence, remain there due to a fear of returning home to a more moribund life.

- Friends churn. Cities like New York, London and Paris are destinations where people end up, Bogotá and Mexico City are places along the way.

- Your view of life and business there gets skewed to underlying group vibes.

Taking the best parts of the "local" and "expat" lives and combining them is critical for foreigners in Latin America. The Guanxi aspects of reputation in Europe delineate between work and social lives, in Colombia, with expats, everything was on the table.

Would I Return?

The opportunities presented by Latin America were invigorating. With no reference points to similar peers, all the usual benchmarking insecurities, like whether I was earning enough, were null and void; I could forge a path without worrying about external validation vanity.

Coming home was more a personal decision along the lines of: Can I see myself settled down here at middle age?

The answer to that was no.

While, at times, selective regret may creep in, Latin America is a place I hope to keep working with and visiting throughout life.